What are my goals for this article?

Before writing this, I was thinking about it from the reader’s point of view, and it came to my attention that the goal of this article might get misinterpreted. So this section is to make sure that doesn’t happen. My goal for this article, is very simple and straight forward. Following this, you’ll have a much better understanding of what shell builtins are, and why you should use them instead of general commands, whenever you can. There is a section that shortly goes through the process of even creating one ourselves. But that should not be considered to be a tutorial. This article won’t teach you how to create a built-ins yourself.

Word of caution

Before moving forward, if you are an experienced Linux user or should I say a more technically advanced user, you might see some sections and think to yourself “Well that ain’t totally correct”, and you will be correct to assume that. I’ll not be going at depths for everything. My goal is to make sure the readers understand the topic in question. That includes new users. That’s why I’ll be hiding smaller details whenever necessary.

What are built-ins?

Before we get into this exact question, I should explain first how exactly a command flow works. Say you’ve opened a terminal, and enter a command like the following

grep 'something important' a-file | wc -l

What is happening behind the scenes? To understand builtins and why you should prefer them, this section is absolutely necessary. But to get to that, first, you’ll be needing to understand a couple more things. I know this is getting deep already right? Bear with me. The following section takes care of the prerequisites.

Prerequisites

What are processes?

Processes are basically running programs. When you start, say a file manager, you spawn a process, named that file manager. Your whole operating system runs consisting of many processes. Processes run alternatively. You might think “Alternatively? What do you mean?”. Well see the processor can’t exactly run one single program to completion, can they? If that were to be true, then you couldn’t even start an operating system, because there are some programs that are always running. We need them to stay that way. And if some process is already running, how can some other program run? Luckily that’s not how they work. The CPU is the master here. CPU determines when and how long one process will be running. And it rotates this, quite fast, which is why we don’t exactly notice anything, we think everything is running at once or simultaneously.

Technically yes, a lot of the processes do run simultaneously of different threads. But that’s not our topic today.

Basically a process is a program, that’s doing something. A program can spawn multiple processes to make its job completion faster. Here’s a fun part to keep in mind, these individual processes have their own memory space. You can understand this analogy by thinking of an unmarried couple. The relationship is a program, each individual is a process. They both have their own house, job, car, etc. Processes of the same program are just like that.

What is exec?

Exec is a system call. Exec takes one argument and simply gives all the resources to that new process. It replaces the current process with the one you passed it.

A system call is basically a keyword that lets us use some of the kernel’s features directly without any abstractions if permissible. You can also think of system calls being features that the kernel lets higher level programs (Like a file manager or text editor) use for a successful operation.

You can test

execwith a shell command named (No surprises)exec. Try runningexec <your-file-manager>in a terminal. You’ll see the terminal closed, and the file manager opened. This is because exec replaced the current process, the terminal/shell prompt with a new one, the file manager.

What happens when you execute a command?

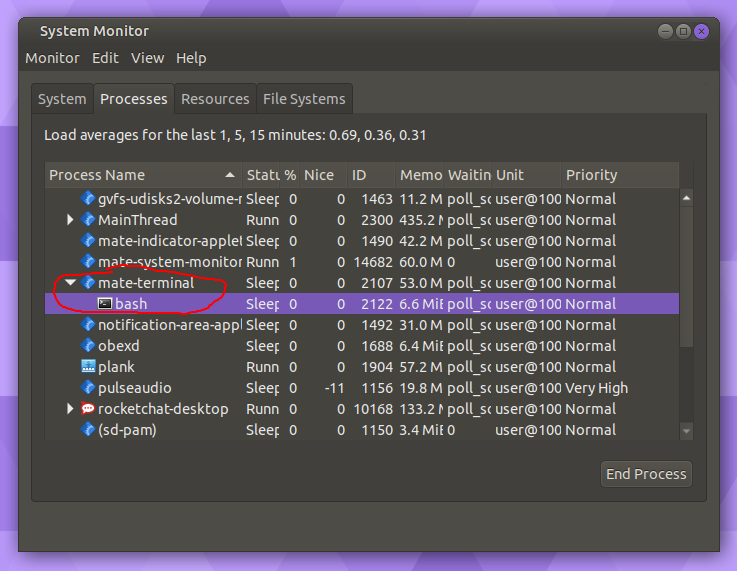

Now that you have the understanding of what processes are and what exec is, the next question is, what happens when we write say cat filename? When you start a terminal, you have a total of two processes. One for the application itself, another for the shell, which in my case is bash. You can check that via a system monitor like the mate-system-monitor. Take a look at the picture below

Now when you execute a command, your shell spawns a new process, then replaces that process with the program you wanted to execute with exec. See the following diagram

missing sorry :p

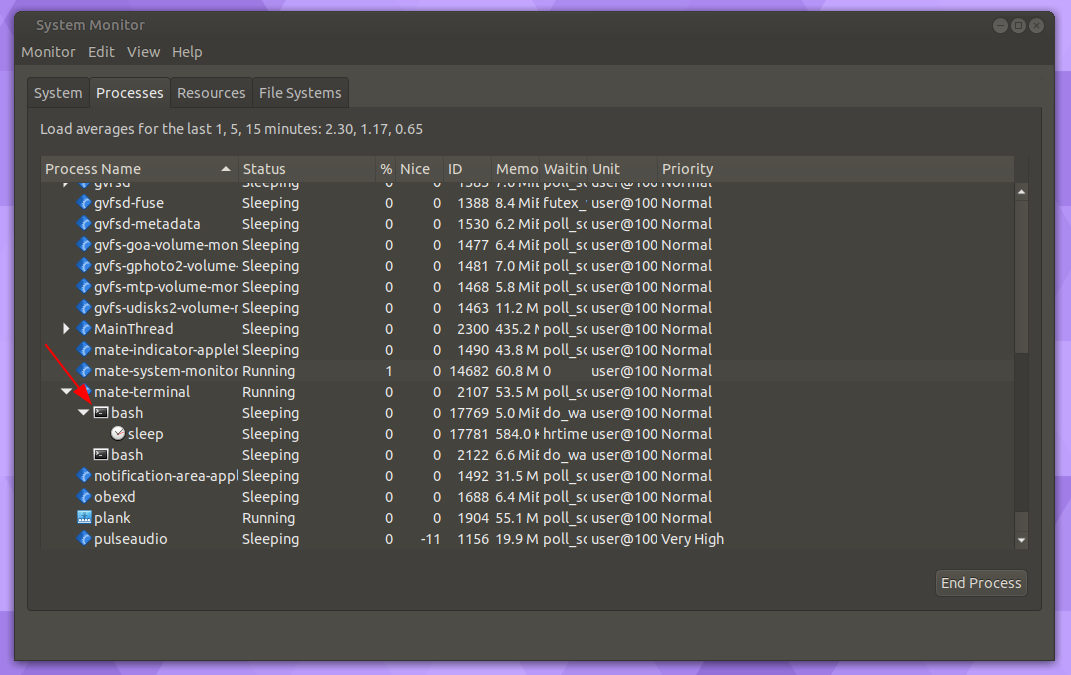

Test this with sleep. Open a terminal, and run sleep 1d. Then open the system monitor, and navigate to the terminal. You’ll see something like the following

So what is a builtin exactly?

For starters, a builtin is not a binary file. You won’t find it in your filesystem. Builtins are the shell’s internal functions. If being specific, a builtin is a 48-byte data structure (Differs between hardware). When you use a builtin, a separate process is not spawned. A builtin to bash is the same as renaming a file is in a file manager. It’s its own feature, it doesn’t have to rely on any other program. This is important because a builtin essentially eliminates the initial system calls that bash had to use if it were an actual binary program. In other words, using builtins results in less overhead, and it’s effectively much faster. Now should we test this? Absolutely!

One fine command that we can use, is echo. There was a time when experienced people in public forums or at other places used to say “Don’t use echo, use printf instead”. This is because printf is a bash builtin whereas echo is an external command. That is not the case anymore. Try running type echo. You’ll see something like the following.

debdut@mate-ubuntu:~/bash-5.0$ type echo

echo is a shell builtin

While it is a shell builtin, we also have our old binary file as well. It’s located at /usr/bin/echo. Use the which command to find it. Now, run the following script

echo=/usr/bin/echo

time {

for i in {0..1000}; do

$echo $i

done

}

This script basically sets the variable echo to the binary echo, then prints the first 1000 numbers. It also keeps a record of how much time the whole process will take. On my computer, here’s my result.

real 0m2.666s

user 0m1.073s

sys 0m1.662s

Now change the variable’s value from /usr/bin/echo to just echo. Rerun the script. I believe you don’t even need to see the results. But still, just for the record,

real 0m0.009s

user 0m0.004s

sys 0m0.005s

It’s much much faster. I do hope now you’re clear on what shell builtins are and why you should prefer them over other binary commands.

Test run, writing my own builtin

The following section is not for everyone. Most are going to be fine with the information provided above. You’ll need to know C if you want to understand any of the source code. You can just copy and paste everything to see the end result as well. Do note that I won’t be explaining the source code much if any at all. So this isn’t a tutorial of any kind.

Install bash-builtins

First, we’ll need a package named

bash-builtins. I’m on Ubuntu 20.04. The package name may vary depending on your distribution. Consult your distribution’s documentation/wiki.sudo apt install bash-builtins -yFix some paths

Next, we’ll need to copy some files over. Execute the following command

sudo cp /usr/include/bash/include/* /usr/include/bash/If you want to remove this package later, you’ll have to manually remove the

/usr/include/bashdirectory. Although it’s around 500K in size. There’s no reason to remove it, is there?Copy and paste the source code

#include <bash/config.h> #include <unistd.h> #include <bash/posixjmp.h> #include <bash/shell.h> #include <bash/builtins.h> #include <stdio.h> int sleep_(){ sleep(5); return EXECUTION_SUCCESS; } char *doc[]={ "Sleep for 5 minutes", 0 }; struct builtin sleep_struct={ "sleep", sleep_, BUILTIN_ENABLED, doc, "Usage: sleep", NULL };Copy the code above, and save it in a file named

sleep.c. This is basically a builtin command, identical tosleep, much simpler though. It does nothing but waits for 5 seconds.Compile the program

Because we aren’t going to rebuild bash, we’re gonna build a shared library that bash will load to memory when needed. Run the following command

gcc -shared -fpic -o sleep.so sleep.cEnable the builtin

Now you can enable the builtin using the

enablebuiltin. This command manages the builtins. Use the following commandenable -f `pwd`/sleep.so sleep

Now you can test the builtin in two ways,

Using the type command Simply run

type sleep. You should see something like thisdebdut@mate-ubuntu:~/builtins$ type sleep sleep is a shell builtinThe older sleep can be found at

/usr/bin/sleep(Usewhich).Compare the process count

Remember previously we used the

sleepcommand to see how there’s a separate process getting generated? Let’s try that out now. Our builtin basically sleeps for 5 seconds. Open the system monitor and the terminal side by side. Then simply runsleep. Now notice the system monitor, there’s no process generated. It was run internally.